This post is a repeat of last year's Memorial Day blog. Just wanted to honor my father-in-law's memory for his service to all of us and the difference he made in so many lives.

It was a different world.

The people living in North Alabama in the late thirties lived simply. Working without ceasing, they had little time or opportunity to keep up with world affairs. When they began hearing talk, sometimes weeks old, about fighting in Europe, about a crazed Nazi killing innocent people, they agreed it was awful, terrible, but it had little to do with them. When the news came that the Japanese had bombed the naval fleet at Pearl Harbor in the Pacific, a place as far removed as the moon to them, they wondered what they would hear next, wondered if this evil could reach their sleepy little river town.

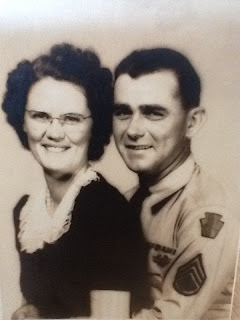

Roy Robertson, 28 years old, was content with his life on the small farm. He and Mary Elizabeth Sharp were married in 1939, and he and his young wife were building their future, starting their journey together. He had just finished his spring planting when he was drafted in June 1942. He reported to Fort McClellan, Alabama, for his basic training.

A strong man who had hunted most of his life, Roy excelled in training, getting numerous badges and listed as a 'Pistol Expert'. Fort McClellan was less than 200 miles from his home, and while Roy was willing to do his part for his country, homesick and heartsick, he found a way to sneak home on occasion, staying until he was escorted back by military police. In October of 1943, he departed Fort McClellan for war-torn Europe. He said afterwards that once he was in Europe, he couldn't sneak back home, so all there was to do was 'soldier'. And what a soldier he became!

The following is part of an article published in a local paper in April, 1945.

Staff Sergeant Roy Robertson, the "one-man mortar squad" who won the Bronze Star medal for heroism in the Battle of the Bulge, is coming home to Waterloo, Alabama, for a 30-day furlough under the Army's rotation plan.

Qualifications for the coveted rotation furlough include length of foreign service, length of combat time, wounds and decorations. Except in the matter of wounds--he has come through a lot of flying scrap metal without a scratch--Sergeant Robertson was the best qualified man in his outfit, Company "M", 112th Infantry.

The Waterloo doughboy came overseas with the 28th "Keystone" Division in October, 1943, and landed in France shortly after D-Day. He was with the "M" Company mortars when they first were committed to action in the St. Lo breakthrough, and pumped hundreds of rounds into the Falaise pocket, where the 28th Division was part of the force which cut off the German Seventh Army.

Moving fast out of the Normandy hedgerows, Robertson and thousands of other Keystone soldiers staged their famed "tactical parade" through Paris on August 29, 1944. While the Parisians cheered in a delirium of joy over the capital's liberation, the doughboys were actually hounding the heels of the Germans as they hiked over the miles of cobbled streets. Next day, Robertson was again dropping mortar shells on the fleeing supermen.

He was on hand when the Yanks took Compiegne, where the first Armistice was signed, and in November he was "zeroing-in" on targets in the dank Hurtgen Forest, scene of one of the bloodiest battles of this war. After Schmidt, where the 28th Division stood off a reinforced Panzer division and two infantry divisions until forced back by sheer weight of numbers and metal, Robertson had a brief respite from battle. For a while the 28th occupied a portion of the "quiet" Belgian front and the men rested--until Von runstedt began his historic counter-offensive.

It was during the 112th Infantry's stand near St. Vith that the Waterloo heavy weapons expert distinguished himself. Operating a mortar alone while his buddies were pinned down by enemy fire, he dropped shells at dangerously closes range and captured a 'hornet's nest' for an estimated 150 Nazi casualties. (The lengthy article continues here with details of other battles.)

When he heard that he had been selected for furlough, Robertson had just completed a gruelling 12-hour march through enemy territory as the 28th Division played its role in the First Army smash across the Rhine. None of Sergeant Robertson's furlough time will be wasted in travel. The deluxe trip, with a stop-over in Paris, is thrown in extra. The 30 days won't start officially until he is almost home on his farm on Route 2, Waterloo.

Roy did make it home on that furlough, exhausted, bone-weary of battles and blood. After digging foxholes in frozen European soil, Roy was delighted to feel the warm, red Alabama soil beneath his feet. He just stayed home after the furlough officially ended. I suppose the military police just didn't have the heart to come and get a hero. They sent him an honorable discharge on October 9, 1945.

After he returned home and life settled around him, he was reluctant to talk about his metals or battles. To him, he just did his duty the best way he knew how.

He never left his farm or community again as long as he lived.

He and Mary raised two daughters and two sons. They had a granddaughter, followed by five grandsons. Illness came to Mary at an early age, and Roy buried his sweetheart in October 1976. He was never the same again.

In October 1979, Roy died suddenly of a massive brain hemorrhage. An American flag was presented to his 9 year-old grandson, our firstborn. The flag was new, the kind presented at military funerals, and it is treasured today. It is just like the flag that flew with the troops on the beaches of Normandy, in the snow in Korea, in the jungles of Viet Nam, and the deserts of Iraq. God bless that symbol of freedom, now and forever.

Thank you, Papaw, for your sacrifice and courage. Thank you for having the fortitude to do your job when fire and bullets were falling around you. Thank you for being an example of strength, strength that is now seen in your children and grandchildren. We remember you with joy.

Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends. John 15:13

It was a different world.

The people living in North Alabama in the late thirties lived simply. Working without ceasing, they had little time or opportunity to keep up with world affairs. When they began hearing talk, sometimes weeks old, about fighting in Europe, about a crazed Nazi killing innocent people, they agreed it was awful, terrible, but it had little to do with them. When the news came that the Japanese had bombed the naval fleet at Pearl Harbor in the Pacific, a place as far removed as the moon to them, they wondered what they would hear next, wondered if this evil could reach their sleepy little river town.

Roy Robertson, 28 years old, was content with his life on the small farm. He and Mary Elizabeth Sharp were married in 1939, and he and his young wife were building their future, starting their journey together. He had just finished his spring planting when he was drafted in June 1942. He reported to Fort McClellan, Alabama, for his basic training.

A strong man who had hunted most of his life, Roy excelled in training, getting numerous badges and listed as a 'Pistol Expert'. Fort McClellan was less than 200 miles from his home, and while Roy was willing to do his part for his country, homesick and heartsick, he found a way to sneak home on occasion, staying until he was escorted back by military police. In October of 1943, he departed Fort McClellan for war-torn Europe. He said afterwards that once he was in Europe, he couldn't sneak back home, so all there was to do was 'soldier'. And what a soldier he became!

The following is part of an article published in a local paper in April, 1945.

Staff Sergeant Roy Robertson, the "one-man mortar squad" who won the Bronze Star medal for heroism in the Battle of the Bulge, is coming home to Waterloo, Alabama, for a 30-day furlough under the Army's rotation plan.

Qualifications for the coveted rotation furlough include length of foreign service, length of combat time, wounds and decorations. Except in the matter of wounds--he has come through a lot of flying scrap metal without a scratch--Sergeant Robertson was the best qualified man in his outfit, Company "M", 112th Infantry.

The Waterloo doughboy came overseas with the 28th "Keystone" Division in October, 1943, and landed in France shortly after D-Day. He was with the "M" Company mortars when they first were committed to action in the St. Lo breakthrough, and pumped hundreds of rounds into the Falaise pocket, where the 28th Division was part of the force which cut off the German Seventh Army.

Moving fast out of the Normandy hedgerows, Robertson and thousands of other Keystone soldiers staged their famed "tactical parade" through Paris on August 29, 1944. While the Parisians cheered in a delirium of joy over the capital's liberation, the doughboys were actually hounding the heels of the Germans as they hiked over the miles of cobbled streets. Next day, Robertson was again dropping mortar shells on the fleeing supermen.

He was on hand when the Yanks took Compiegne, where the first Armistice was signed, and in November he was "zeroing-in" on targets in the dank Hurtgen Forest, scene of one of the bloodiest battles of this war. After Schmidt, where the 28th Division stood off a reinforced Panzer division and two infantry divisions until forced back by sheer weight of numbers and metal, Robertson had a brief respite from battle. For a while the 28th occupied a portion of the "quiet" Belgian front and the men rested--until Von runstedt began his historic counter-offensive.

It was during the 112th Infantry's stand near St. Vith that the Waterloo heavy weapons expert distinguished himself. Operating a mortar alone while his buddies were pinned down by enemy fire, he dropped shells at dangerously closes range and captured a 'hornet's nest' for an estimated 150 Nazi casualties. (The lengthy article continues here with details of other battles.)

When he heard that he had been selected for furlough, Robertson had just completed a gruelling 12-hour march through enemy territory as the 28th Division played its role in the First Army smash across the Rhine. None of Sergeant Robertson's furlough time will be wasted in travel. The deluxe trip, with a stop-over in Paris, is thrown in extra. The 30 days won't start officially until he is almost home on his farm on Route 2, Waterloo.

Roy did make it home on that furlough, exhausted, bone-weary of battles and blood. After digging foxholes in frozen European soil, Roy was delighted to feel the warm, red Alabama soil beneath his feet. He just stayed home after the furlough officially ended. I suppose the military police just didn't have the heart to come and get a hero. They sent him an honorable discharge on October 9, 1945.

After he returned home and life settled around him, he was reluctant to talk about his metals or battles. To him, he just did his duty the best way he knew how.

He never left his farm or community again as long as he lived.

He and Mary raised two daughters and two sons. They had a granddaughter, followed by five grandsons. Illness came to Mary at an early age, and Roy buried his sweetheart in October 1976. He was never the same again.

In October 1979, Roy died suddenly of a massive brain hemorrhage. An American flag was presented to his 9 year-old grandson, our firstborn. The flag was new, the kind presented at military funerals, and it is treasured today. It is just like the flag that flew with the troops on the beaches of Normandy, in the snow in Korea, in the jungles of Viet Nam, and the deserts of Iraq. God bless that symbol of freedom, now and forever.

Thank you, Papaw, for your sacrifice and courage. Thank you for having the fortitude to do your job when fire and bullets were falling around you. Thank you for being an example of strength, strength that is now seen in your children and grandchildren. We remember you with joy.

Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends. John 15:13

Comments

Post a Comment